City of Collective Memory

Grieving a place is not unlike grieving a person. This past week I’ve found myself seeking a deeper empathy for the devastated survivors of the recent fires in Los Angeles. It’s brought me to recall Santa Cruz’s 1989 earthquake (Loma Prieta) that flattened my vibrant downtown in a thirty seconds. Growing up, I had never really addressed the loss of my downtown until I found myself reading, subconsciously perhaps, books from people who’d also lost their home turf: Edward Said’s Jerusalem in Out of Place, Vladimir Nabokov’s St. Petersburg in Speak, Memory, Hayden Herrera’s Cape Cod in Upper Bohemia to mention a few. In college I ended up getting a degree in Urban Studies, and went to graduate school for City Design and Social Policy. A reoccurring theme in my research was the disorientation experienced by the survivors of the bombing of Nagasaki or Dresden in WWII: how a physical loss of place impacts the patterns and rituals of a community. These devastated war zones and my evaporated downtown Santa Cruz had some one thing in common: a ‘before’ worth treasuring. I found solace in remembering the lost Santa Cruz with friends, like a child who has lost a parent: “did I imagine that, or did that really happen?” This corroboration has been a kind of balm. A place we return to in our minds. A city of collective memory.

The Earthquake

In October 1989, the catastrophic Loma Prieta Earthquake destroyed the majority of downtown Santa Cruz -- a world that that had raised, educated, and taught me how living well (health, culture, community) should feel. I was fourteen when the earthquake struck. The initial dramatic jolts struck the tennis court where my high school team was hosting a match. I remember the green rectangles of tennis court paving undulate like a blanket being made on a bed. Our tennis coach screamed, “Keep playing, girls! It’s just a tremor!” while Downtown Santa Cruz just blocks away erupted in flames from broken gas lines, brick buildings toppled into massive piles on the street, cultural institutions, businesses, restaurants, shops were mangled beyond recognition. Our coach had been dead wrong: the quake registered at 6.9 on the Richter scale, flattening freeways and bridges north of us in San Francisco. Soon after the big jolts, our parents arrived one by one to whisk us home. Fourteen was young enough to have feet-of-clay about my hometown; I was not yet cognizant of Santa Cruz’s often sordid underbelly (it had been an untamed hippie stronghold since the sixties, with a huge drug culture.) Fourteen was, however, old enough to have banked in my memory a rich repository of experiences rooted in a place that was changed forever, in thirty seconds of undulating earth.

“Every memory unfolds in a spatial framework.” – Christine Boyer, City of Collective Memory

The Cooper House

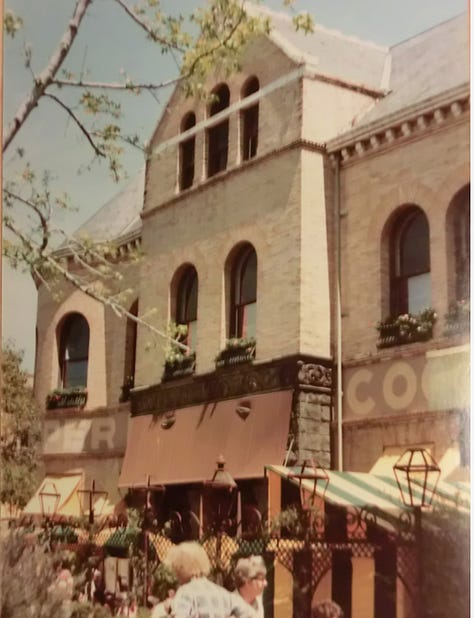

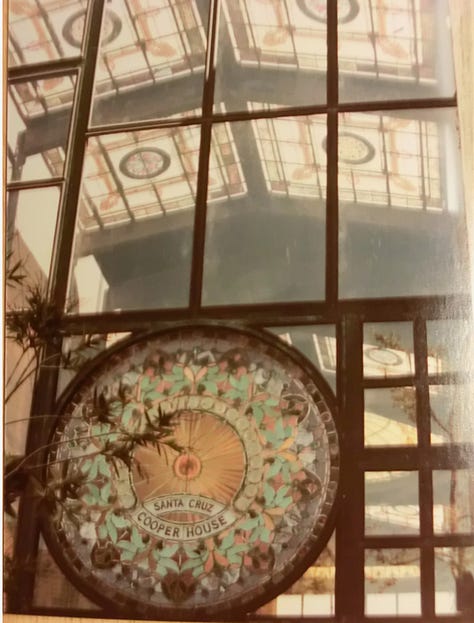

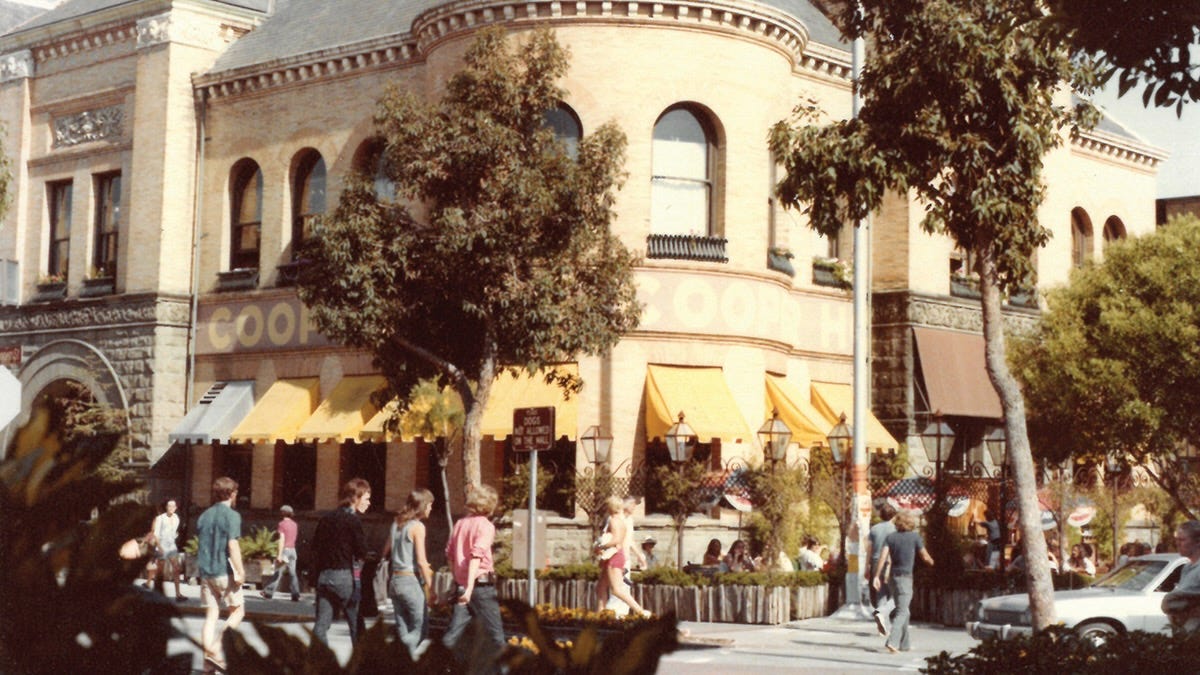

One building destroyed in the disaster still makes my eyes sparkle. The Cooper House was the undisputed crown jewel of The Pacific Garden Mall (an downtown esplanade more akin to Las Ramblas in Barcelona than an American mall per se.) The Cooper House was a massive, square 1918 building rendered in Richardsonian Romanesque with COOPER HOUSE emblazoned across its fat midriff. It managed to be both urbane but casual, in a quintessentially Beachtown Bohemian way. A sort of multi tenant proto-mall, the Cooper House housed many local businesses, not unlike like a London shopping arcade, but stacked vertically rather than down a corridor. The edifice had originally been a courthouse and communicated that caliber of architectural seriousness. It appeared heavy and robust in comparison to its neighboring Victorian wood structures along The Pacific Garden Mall. Repeating stone arches like the quad at Stanford University and wavy Victorian window panes graced the handsome exterior. You entered via a sandstone staircase to a mezzanine, where several small shops shared a hardwood floor interior hallway lit by an extraordinary stained glass dome overhead. Having ascended the stairs, you were greeted by the scent of caramel apples from an old fashioned candy shop that dominated the hallway, thereby generating a snaking line of salivating local kids in board shorts. Through old stained glass window panes, we studied neat trays of chocolates, salted pepitas and non-pareils. Down in the basement level, I recall a popular sticker shop -- all the rage with early eighties youth -- and a toy shop that specialized in kites. Which is to say, to a child The Cooper House had a hint of the allure of Disneyland, but in your own downtown where your mom did errands.

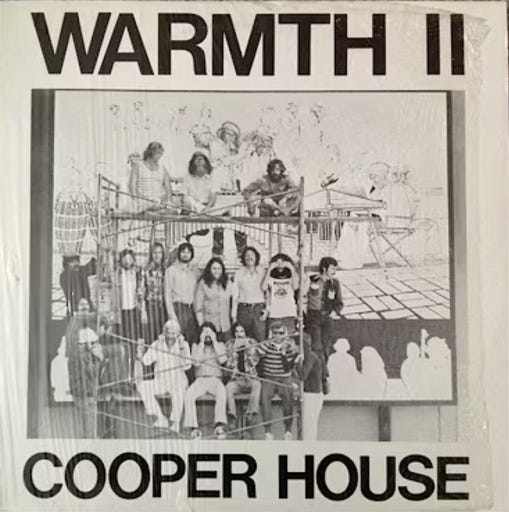

Architectural details aside, there was a specific music that emanated from The Cooper House: the sound of a vibraphone. More often than not, the ground floor café at the Cooper House hosted a live band called Warmth Jazz Band (Don McCaslin) playing West Coast “cool jazz” at its sidewalk café. The café spilled toward the street with cheerful Cinzano umbrellas. Adults sat under them drinking beer and eating open-face sandwiches. The sound of the band’s vibes reverberated down the Pacific Garden Mall, like a soundtrack for the dappled sunlight. This weightless, ethereal music defined the mood in on The Pacific Garden Mall the way an Ennio Morricone film score makes a scene without dialogue poignant. It lent tenderness. It was in this way that the Cooper House offered itself — via its music — to the entire street.

The Loma Prieta earthquake damaged the Cooper House so severely that it was condemned: it was deemed too far gone to even examine inside, let alone attempt salvaging it. It was subsequently torn down, along with the majority of the other buildings on Pacific Avenue that we knew and used on a daily basis. Ballet school crushed. Bookstore evaporated. Two department stores flattened. The town valiantly worked to keep businesses solvent, and opened up a parallel retail universe of massive hardshell tents in the municipal parking lots. But it wasn’t the same.

We are attachment animals

I still struggle, 35 years later, with the notion that The Cooper House, and the rest of The Pacific Garden Mall cannot be revisited. I am still attached to it’s memory. As an object, The Cooper House was an gesture of generosity. Even if you grew up in a cheap 1950s spec house in town, The Cooper House was a building that raised your standards. It seeped into your subconscious and informed your taste for random-width wood floors and rough stone archways that envelop you in ceremony. In a California that is often on the cusp of everything new, we absorbed from The Cooper House an awareness of hand-wrought construction and old school craftsmanship. Alain de Botton, in The Architecture of Happiness, explores the impact of the architecture that we experience in childhood. We are affected by osmosis, he argues, via the design around us. Design impacts us psychologically: operable windows make us feel free, high ceilings make us feel small and sometimes awe-struck, and so on. From the Cooper House we learned that some buildings elicit a feeling of belonging that can be felt in the building’s music and scent. We learned that a wood banister felt good under your small hand, and that stone steps make a pleasant scratchy sound against the sole of your shoe. Most pointedly, we learned that even the most monolithic structures can crumble to dust when Mother Nature shakes her skirts. Loma Prieta taught us that buildings can die too. And that elegance can be casual and playful and light. Like the vibes.

Beachtown Bohemia is paywall free. You can support me by liking this post (heart button at the top) and sharing it with anyone you feel would appreciate it.

Very nice, such memories. The “new” downtown just doesn’t hold up, 35 years later I’m still disappointed whenever I go there.

Structures have a soul. 🕍