Growing up near a famous surf break is like living next to Carnegie Hall. If it’s showtime, you brace yourself for the heaving crowds that descend en masse to your neighborhood. In Santa Cruz, showtime was typically in the winter season, when the swell is big and surf contests, like the O’Neill Coldwater Classic, drew international legends and spectators to your own back yard. West Cliff Drive, a block from my childhood house, winds its way along the entire west side of Santa Cruz from the Boardwalk to the northern most edge of town, where it terminates at a state park. It is a curving two-lane street with a wooden fence on the cliff side to keep you from falling 70 feet to the jagged rocks below. Steamer Lane is about midway along the length of West Cliff: it sits on the promontory of the Monterey Bay’s northernmost point, where the Pacific Ocean meets the marine sanctuary. The Lighthouse, the west side’s most prominent oceanside landmark, sits on a jutting cliff above Steamer Lane. In winter the number of surfers in the water doubles – as do the bystanders on the cliffs watching the show below.

Across from Steamers was a nature reserve called Lighthouse Field State Park. As a child I likened this landscape to the images of Africa I had seen on Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom: a large flat expanse of dry yellow grasses punctuated by massive misshapen cypress trees and clumps of pampas grass. As we drove home, it was always Carnegie Hall (Steamers) on the left and Africa on the right.

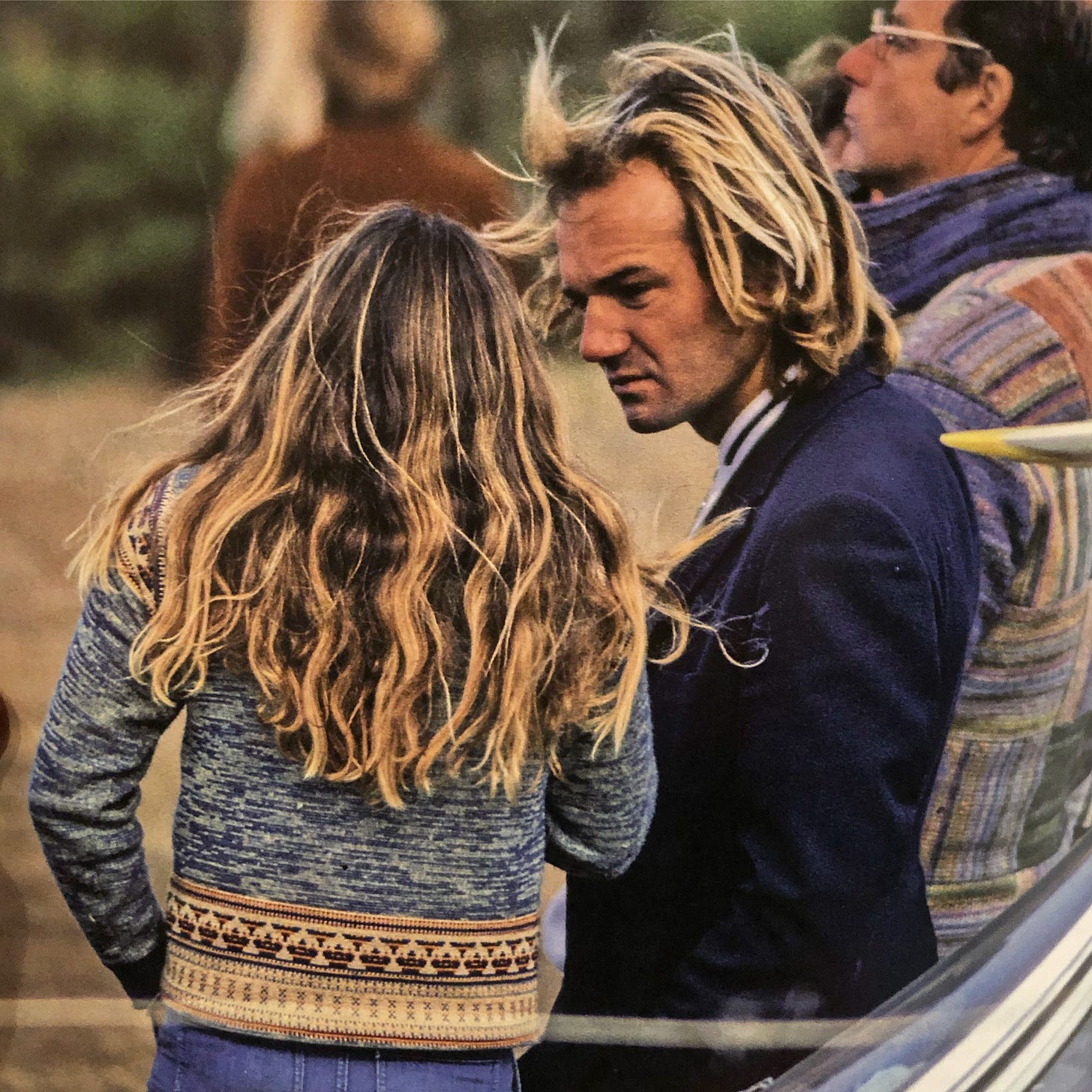

There was a full operatic scene on the cliffs at Steamer Lane that went beyond what happened on the water. Camper vans and surf mobiles laden with boards lined the parking spots at the cliffs on either side of the Lighthouse. Gorgeous wet-headed men with towels around their waists tantalized the female population at the trunks of their cars as they slipped out of wetsuits and into dry clothes. Sometimes you’d catch a flash of bare buns. These men were admired by everyone as fervently as the surfers themselves admired the wet dogs in back of their Datsun pickup trucks.

The center of the Steamer Lane universe was the top of the stairs that lead down to the ocean. This is where the surfers paddled out. There was always a cluster of local power at the top of the stairs: seasoned regulars, fiercely maintaining their territory – in other words, acting as bouncers for any out-of-towners or “kooks” (inexperienced surfers.) These were tawny-necked men, with tousled hair and beautiful backs that sloped in musculature formed by their hours of endless paddling. If they weren’t in the water – on stage at Carnegie Hall – they were back on the cliff watching the next guy take the stage. A brief interruption – a friend, a beautiful woman, a quick bathroom trip -- then it was eyes back on the water.

By the early nineteen-nineties I sensed a tonal shift in the surf culture in beachtown bohemia. The formerly golden yellow, happy, stoner surfers seemed to morph into a hard-edged, darker, amphetamine-fueled iteration of their former selves. You felt it energetically along the cliffs if you were out for a jog: angrier music emanated from their rust-rimmed cars, there was more black clothing, spiky bleached hair, more scowling. Gone were the jolly stoned Spiccolis: these were surfers on hard drugs. I had classes in high school with some of the most celebrated of these surfers. They heroically charged big waves up at Mavericks (just up the coast) with a drug-fueled confidence that amplified their existing skill and cojones. Some of these classmates made the covers of surfing magazines, but backstage at Carnegie Hall the culture had grown angular. Punk rock and angst, neoprene and methamphetamine.

Beachtown Bohemia is paywall free. You can support me by liking this post (heart button at the top) and sharing it with anyone you feel would appreciate it.

Meth hit the Santa Cruz surfing tribe hard.

Vivid attention to details, with interesting writing that flows well - nice to read