My favorite babysitter growing up was the teenage daughter of a celebrated Santa Cruz surfboard shaper. Sundee looked like she walked out of a Botticelli painting and slipped into a pair of Op shorts. She had big, wavy gold-flecked hair and long, glossy bronze legs. She would cheerfully spend hours sitting cross-legged with me on the living room floor coloring paper dolls. Sundee would divulge, in hushed tones, the techniques that surfers used to stay warm in the icy Monterey Bay: “Via,” she whispered conspiratorially, “they pee in their wetsuits.” Having older, Manhattanite parents who did not surf, I looked to Sundee as my interpreter of the culture around me that I did not feel quite a part of. She, progeny of local surf royalty, was raised inside the walls of this house of cultural nuance. But mostly I liked how she spoke to me in a soft voice.

One weekend I knew something was off when Sundee arrived at breakfast and stayed an entire day. My mother had received a mysterious call early that morning, and promptly got dressed up in: Ferragamos, a helmet of hairspray, and an aggressive quantity of Chanel No.5. As I got older I knew this to be her sartorial suit of armor -- the battle uniform she relied on when required to do something heartbreaking. I sensed that something serious had happened, but my mother remained opaque.

It had been a dark era in my little family. Earlier that year my erudite, gregarious father had been diagnosed with a rare case of early-onset dementia at the age of fifty-three: we had been forced to move him out of our house and into a facility in Menlo Park, an hour drive from Santa Cruz. There was, at the time, no place to care for someone in his state in Beachtown Bohemia. On Sundays my mother and I drove together to see him: I remember the clip clip of her patent leather heels down the long institutional hallways lined with orange vinyl reclining chairs. We’d pretend to be jolly and whisk him off to a steakhouse and order him martinis. We sought to remind him that he had a family that cared about him. That he was a man of martinis, not a man of orange vinyl reclining chairs. By fourth grade he didn’t remember my name.

My mother drove by herself to see him that morning, however. And Sundee had agreed to babysit. That morning in Menlo Park, in a momentary shard of clarity, my father had escaped from the dementia ward and slipped out to the freeway off ramp. He flung himself over the overpass railing onto the Highway 101 traffic below in a lucid act designed to spare himself, and us, from his inevitable demise. Six-foot-two and barrel-chested, when the ambulance got to him it was determined that he’d somehow only broken an arm.

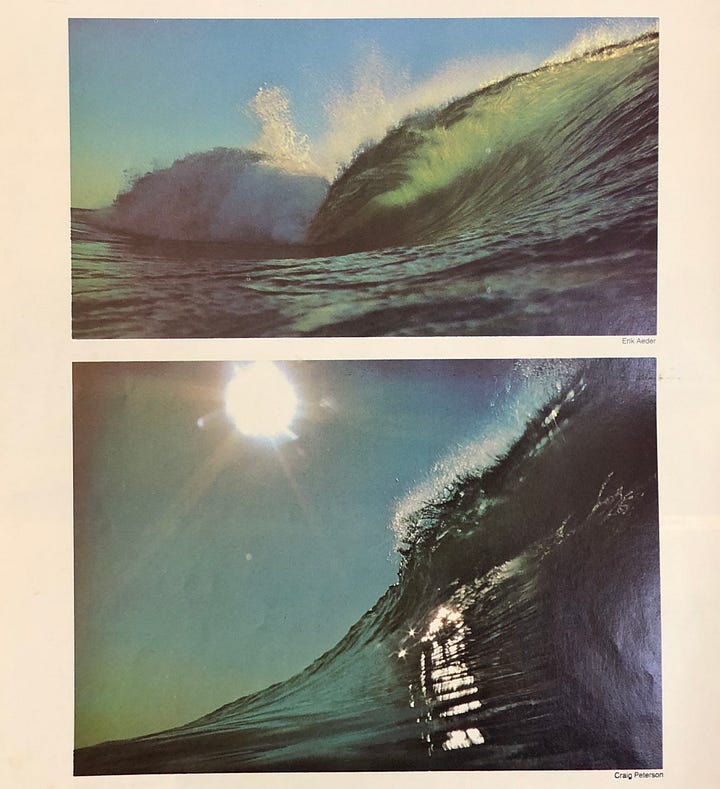

Children have a sixth sense for disquiet. I knew something was awry. A calm came to me that night from two auditory directions. In one ear, the voice of Sundee reading to me, sweetly. In the other, I lay in receipt of the ocean's steady metronome outside my window. Wave, crash. Wave, crash. The ocean -- grand and masculine and comforting -- felt familiar, even fatherly. If fado, the haunting Portuguese folk songs, are for mournful widows who sing out to the sea, the ocean was fado inverted for me. The sea singing to the mourner.

Beachtown Bohemia is paywall free. You can support me by liking this post (heart button at the top) and sharing it with anyone you feel would appreciate it.

Beautifully written - thank you for sharing this personal experience.

Oh my Olivia. I couldn’t breathe.I was taken to a place. Thank you for sharing something so meaningful and personal.