My mother’s friends, the beach town literati, were a glamourous group. They wore flared trousers under their caftans. In their straw bags there might be: a Maybelline lip gloss, a Chinese silk change purse, a tortoiseshell comb, and a New Yorker folded in half along the long edge that doubled as a fly swatter. In their sensible Toyota sedans were Vivaldi and Miles Davis cassettes and wax paper bags of sliced plums for the sunburned kids in the backseat. On their stoves were boiling pots of Soup Au Pistou (for years I mistakenly assumed this meant “soup of pea stew” in French) and in their fridges, chilled bottles of Dos Equis. In the evening, after dinner, these women could be found tucked into the corners of their tailored sofas reading John Updike, with their Pappagallo espadrilles tossed on the sisal next to the cat. They were not striving. Their glamour was sourced from somewhere more sophisticated, wry, and bookish. A substance permeated their allure (“What are you reading?” they might demand to know), and a worldliness directed their interests (“That Zarzuela in San Francisco looks like a good time.”) Most other California beach town women, I learned, were not necessarily like this. At the time I was embarrassed to have a mother who was eccentric and unlike the fit, perky surf moms in trendy Dove shorts watching their kids at the cliffs.

What I now recognize is that my mother and her friends had a vanity that was deeply associated with things outside of their appearance. And I see this, with clarity, as one of the greatest gifts I could have been given. Yes, they were vain – painfully so in some instances. But this vanity lay in how they were perceived as readers, cooks, thinkers, doers, conversationalists, and experts in their field -- all aside from how they looked. I will start with the example of my mother’s best friend Harriet.

Harriet was slinky and sexy and smart like a cat rubbing at your ankles. She was my mother’s oldest friend in Santa Cruz, their friendship dating back to the late fifties in San Francisco, where the two had met in a booth at Tosca in North Beach. (Both of their boyfriends were writers, and North Beach was ground zero for the beatnik writers of the city at that time.) Like my mother, Harriet was originally from New York City. Harriet was petite and busty with shiny gold hair that she sometimes permed like Barbara Strisand. Raised on the Lower East Side, she escaped the rigid confines of her conservative parents, got herself a college degree and embarked on a life out West. Harriet was, even through the eyes of a child, a fox. She had the voice to go with it too, like the heroine of Lawrence Durrell’s Justine: a sultry fine-boned jewess of palpable desirability. At dinner one night when I was little, she asked me if I could touch my tongue to my nose. I couldn’t. But I knew as I watched her perform this trick of oral acrobatics that, to the adults at the table, her skill was a not-so-opaque display of prowess.

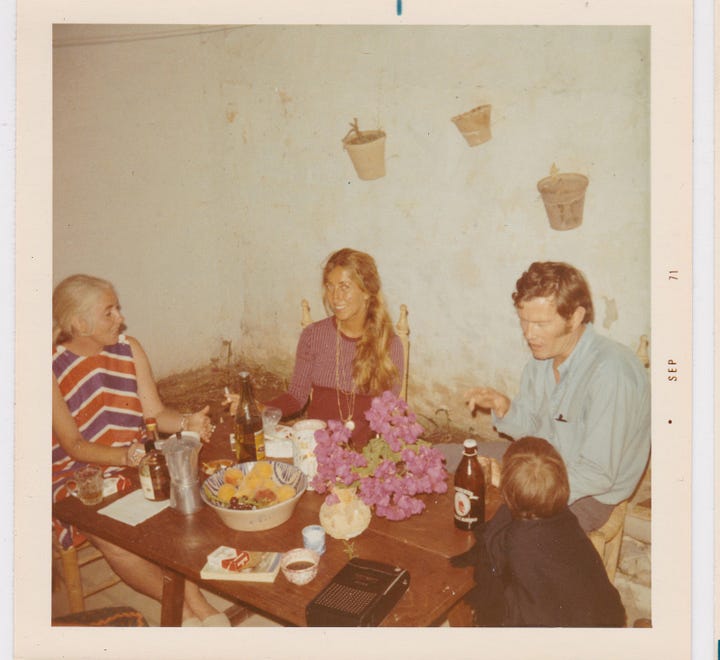

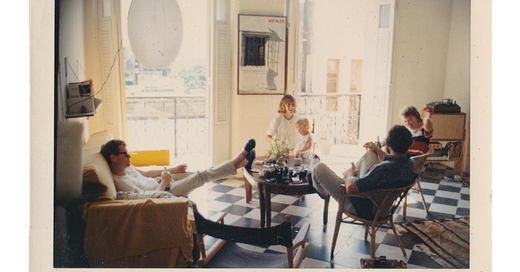

Harriet and her husband (a gorgeous and talented writer) embodied the bohemian ethos of the sixties and seventies. Harriet and John had taken off to live in a writer’s colony in Andalusia for a decade, eventually returning to California to ride the economic upswing of the eighties via Harriet’s successful realty practice in boom-town Santa Cruz. Harriet drove around town in a chic (and rare) Maserati-Volvo and hosted two heaving parties a year: one at Fourth of July and another at Christmas. The Deck’s parties were the kind where there might be a longshoreman and the UCSC Provost playing horseshoes out back. Or a noted sculptor, a cook and an octogenarian Marine Biologist shucking oysters in the kitchen. Their house, a fine Victorian that she treasured, was an expressive vessel for how they lived, but was never fussed over. Her vanity was, rather, invested in the milieu of who was invited, her excellent cooking, and the promotion of her local open space preservation efforts – not the shape of her derriere or the opulence of anything.

Harriet was a beauty, but her primary vanity lay in her intellect: she had built her business from nothing, and parlayed her several decades of success connecting people to property into a role as one of the town’s most ardent environmental activists and fundraisers, in particular UCSC’s Institute of Marine Sciences which she was instrumental in shaping. She was a powerful woman who just happened to be beautiful. And I noticed that. Harriet may go down in history as the least bourgeois real estate person that has ever been.

I am reminded of a book that a beloved older female friend once gave me called Women and Desire: Beyond Wanting to be Wanted by Polly Young-Eisendrath. It was one of those books that resulted in a paradigm shift. The book’s thesis is that women culturally inherited a false premise that, to be deemed worthy, they must become an object of desire – accumulating the admiration of men (a.k.a. the male gaze.) Young-Eisendrath’s call to action is that women must become the subject of their own desire in order to live fully realized, empowered lives: women must fall in love with their interests, passions, work – all topics that ignite a woman from the inside, rather than offer that power to a man. God, Harriet did this so beautifully. She was in love with a world that she herself had built, and had fun being a woman. Observing Harriet revel in the fruits of her labor was an education indeed.

Below is a draft prose piece on this topic of women and desire. It’s something I think about a lot as a creative, a mother of daughters, and a humanist.

Beachtown Bohemia is paywall free. You can support me by liking this post (heart button at the top) and sharing it with anyone you feel would appreciate it.

Now this is the kind of vanity I can get behind! Thank you for transporting us to this magical place.

Love this! I seem to recall Zarzuela also....but was it a restaurant??