In my earlier description of The Men of Beachtown Bohemia , I sought to describe a certain breed of Santa Cruz man — the fathers of my friends — who left a deep impression on me. Here I’d like to introduce you to three of these exemplary West Coast men. By osmosis, each one taught me what it meant to be a Californian, a working-creative, and an original. In a contemporary world where young men are fed over-the-top machismo and caricatures of ‘leadership’, I offer you here three men who were as stylish as they were humble, as introspective as they were dazzling party-people, and as kind as they were accomplished.

Tom Rickman

One of the key members of my parent’s posse, the Santa Cruz beach town literati, was a screenwriter named Tom. He was the father of my closest friend. While not a surfer, Tom held a similar captivating, gritty soigne and leathery face. He was originally from Kentucky and had a slow southern gentlemanliness about him and thick hair like a Kennedy. At the end of a party, he’d often be coerced by everyone into dragging out his guitar and singing Appalachian ballads. Tom was an incredibly accomplished writer. His screenplay for the film Coal Miner’s Daughter (1980) was nominated for an Oscar. When I was in fourth grade, I remember sneaking out with his daughter to Tom’s little writer’s cabin in the woods on their property to peek at his collection of old Mad Magazines on the bookshelves — which we knew had naughty cartoons. He wrote original songs for our Brownie troop. On our elementary school class’ Gold Country Field Trip, I distinctly remember Tom in attendance ‘round the campfire wearing a Talking Heads/ Stop Making Sense t-shirt and Converse high tops. The profound cool of this man was palpable to us all and cannot be overstated. Coolness aside, he was gentle with us kids — asked us questions about our drawings or our opinion of the song playing on the car radio. Tom epitomized the kind of smart, original, soulful California creatives that made up my parent’s social set in the Santa Cruz of the late seventies and early eighties. Tom made adulthood look like a damn good time.

Bob Scowcroft

Bob Scowcroft was younger than my parent’s arty friends but could socialize seamlessly with pretty much anyone. He worked in the same department at the University as my mother and they became office comrades. Bob was energetic and iconoclastic with stringy blonde hair and a big, fabulous laugh. I remember him always in a brown leather bomber jacket. Bob taught classes on something new and edgy circa 1986 called ORGANIC FARMING (he is now considered one of the father’s of the California Organic Farming movement) and had a broad, refined ear for music. After a lunch-break tip from Bob, my mother came home one night with the Paul Simon Graceland album, the sole contemporary music album I remember her buying my entire childhood. (My parents, old New Yorkers/beatniks had a record collection of jazz, classical, Cream, Odetta and other staples of high-bohemianism — but absolutely nothing new since maybe 1978. Having the Graceland album on our turntable right when it came out made me proud, as if my mother were sporting trendy jeans. Bob came to my rescue in 6th grade when (because of my father’s long term illness) I was the only kid without a dad signed up for the Father’s Day class softball game. Bob arrived behind the backstop that June afternoon, young and suave in sunglasses to spare me from the shame and embarrassment of my family’s existence on the margins of normal. I don’t remember if Bob hit a home run, but he looked better than the other dads: serving up high-fives, slinging 80s slang words, and making me feel not so outre. Many times since I have been overcome with emotion remembering Bob’s generosity in showing up as my stand-in father that day. It was an act that sewed a perfectly functional MacGyvered patch over the hole in my eleven-year-old heart.

John Deck

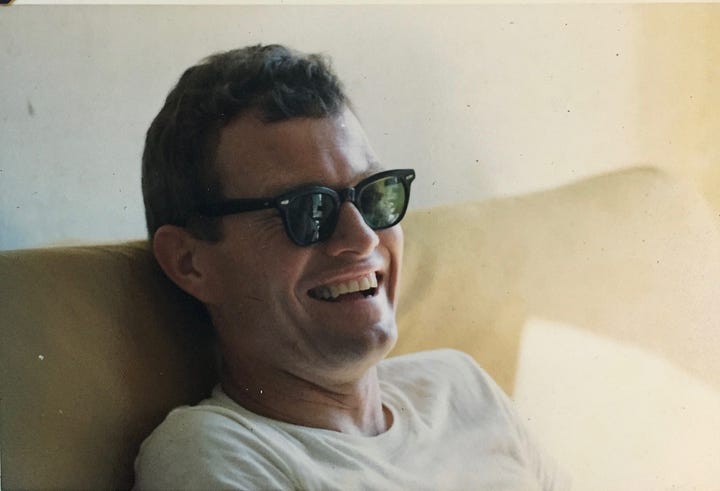

I probably romanticize writers because I grew up with John Deck in my orbit. He looked like Chet Baker and spoke in a low musical voice full of wry humor. He had a curious diction I could never pin down: SoCal casual through the filter of a crisply-annunciating stage actor. He spoke as precisely as he wrote. John was a gentleman bohemian and a reader and an open-minded Californian whose brother was a prominent longshoreman. Born in Long Beach in the 1930s, John served in Korea and caught the travel bug. He was the first in his family to go to college (Masters in Creative Writing from SF State) and became a damn good writer. John became the kind of writer who maybe didn’t sell a lot of books but whose Kirkus Review, “A very funny, aware, accomplished collection” (for Greased Samba & Other Stories, 1970) solidified his place in the writer’s world.

My mother had met John at the bar Tosca, in North Beach, in the late fifties, sitting in a red leather booth with his bombshell girlfriend Harriet and two friends from his Master’s program: Leonard Gardner & Clancy Carlile. All three men went on to lauded careers in fiction and screenwriting - including gigs reviewing books for The New York Times and writing stories that became John Huston films and Clint Eastwood vehicles. The writers formed a sort of sacred posse of midcentury book-fueled seekers. John and Harriet and Anne-Marie followed each other around the world from Puerto Rico (John was teaching Creative Writing in San Juan) to Spain where they established a writer’s colony in the 1960s. And then back to Santa Cruz where they set up shop for the second half of their lives, building a community of creatives and worldly bohemians who defined, for me, what sophisticated adulthood looked like. Big old Victorian house, parties with fresh oysters and wine in big buckets of ice and horseshoes out back by the redwood trees. Living rooms with high ceilings and books books books and beat up old sofas and a wall of records and old framed posters of Jules et Jim. If being an adult meant getting to live like John Deck, I was done with childhood.

On a more personal note, John — like Bob — showed up when I needed a dad-figure. He showed up, in his white Panama hat, to my high school Homecoming games, my college graduation, my wedding. John was refined, erudite, and sharply observant — just like his writing.

I learned from these three that admirable men knew their horseshoes and their Beckett, their courtliness and their creative work moxy, and were confident in their gentleness. I’m thankful to have been offered their example, witnessed their sparkle, and belonged to their community.

Today’s feature from the Studio Shop

In the summer of 2020 I acquired 200 vintage surf magazines from James O’Mahoney, legendary skateboarder, surfer, publisher, and founder of the (now shuttered) Santa Barbara Surfing Museum. In studying the magazines, I was struck by the ocean as captured through film rather than digital photography. Each orb is a study of these blues, which is then paired with a short prose vignette that speaks to my affection for coastal California. (Steamer Lane is a famous break in Santa Cruz.) Art measures 7” x 9.5” and ships flat, unframed.

Beachtown Bohemia is paywall free. You can support me by liking this post (heart button at the top) and sharing it with anyone you feel would appreciate it.

This writing is powerful and so inspiring. This makes me take a look at myself and how I could be present for someone. Thank you Olivia.

Wonderful. Confirms my belief that wonderful men continue to exist.